The government actually funded the research into fracking that lead to the technology we currently use that gives the U.S. a competitive edge in the industry.

The technological revolution allowing for the cheap extraction of natural gas from shale occurred thanks to more than three decades of government subsidies for research, demonstration, and production, a new Breakthrough Institute investigation finds. The lesson from the shale gas history is that government investment in innovation can, over time, commercialize and deploy technologies that make yesterday's less-efficient, dirtier, and more expensive technologies obsolete. The successes achieved by federal agencies partnering with private industry to design, demonstrate, and commercialize shale fracking should tell us something about the ongoing federal support for solar, wind, nuclear, and other zero-carbon energy technologies. Just as it did with personal computers, cell phones, jet turbines, and nuclear power, federal investment in innovation can lead the way towards American technological leadership, international economic competitiveness, and a cleaner energy future.

The technological revolution allowing for the cheap extraction of natural gas from shale occurred thanks to more than three decades of government…

thebreakthrough.org

Mitchell learned of shale’s potential from the Eastern Gas Shales Project, a partnership begun in 1976 between the Energy Department’s Morgantown Energy Research Center and dozens of companies and universities that sought to demonstrate natural gas recovery in shale formations and to map and test core samples from unconventional natural gas deposits. Starting in 1981, Mitchell’s geologists drew heavily on that research to guide their explorations.

Mitchell’s success depended on a revolution in monitoring and mapping technologies driven largely by government labs. The new technologies allowed geologists to more precisely map and understand shale formations. In 1991, Mitchell asked the publicly funded Gas Research Institute, then funded by a tax on gas production, and the Energy Department for help. Sandia National Labs provided Mitchell with many critical microseismic tools. Mitchell also benefited from 3-D imaging, which the Energy Department had long supported.

--

The Energy Department also pioneered better drill bits and air-based drilling, which better protected the gas assets of geological formations. And in 1991, the publicly funded Gas Research Institute recommended that Mitchell experiment with horizontal drilling and even subsidized his first horizontal well.

Ultimately, Mitchell and other gas developers’ decision to spend millions of dollars and nearly two decades pioneering techniques that few thought would result in commercially viable extraction is less quixotic than it might have appeared. The federal government generously subsidized drilling for non-conventional gas throughout the 1980s and 1990s, when oil and gas were cheap. While the rise in natural gas prices in the late 1990s sparked the shale gas revolution, it was the federal non-conventional gas tax credit that made Mitchell’s experimenting possible in the early years, when there was no market for more expensive shale gas.

Giving the federal government credit where it is due takes nothing away from Mitchell, who was determined and tenacious. But the lesson of the shale gas revolution is that we should not be so quick to judge government investments in energy technology. Between 1978 and 2007, the Energy Department spent $24 billion on fossil energy research. Billions more were spent through the Gas Research Institute and non-conventional gas tax credits. Those investments were widely panned as a failure during the ’80s and early ’90s, when gas was plentiful and cheap.

en.wikipedia.org

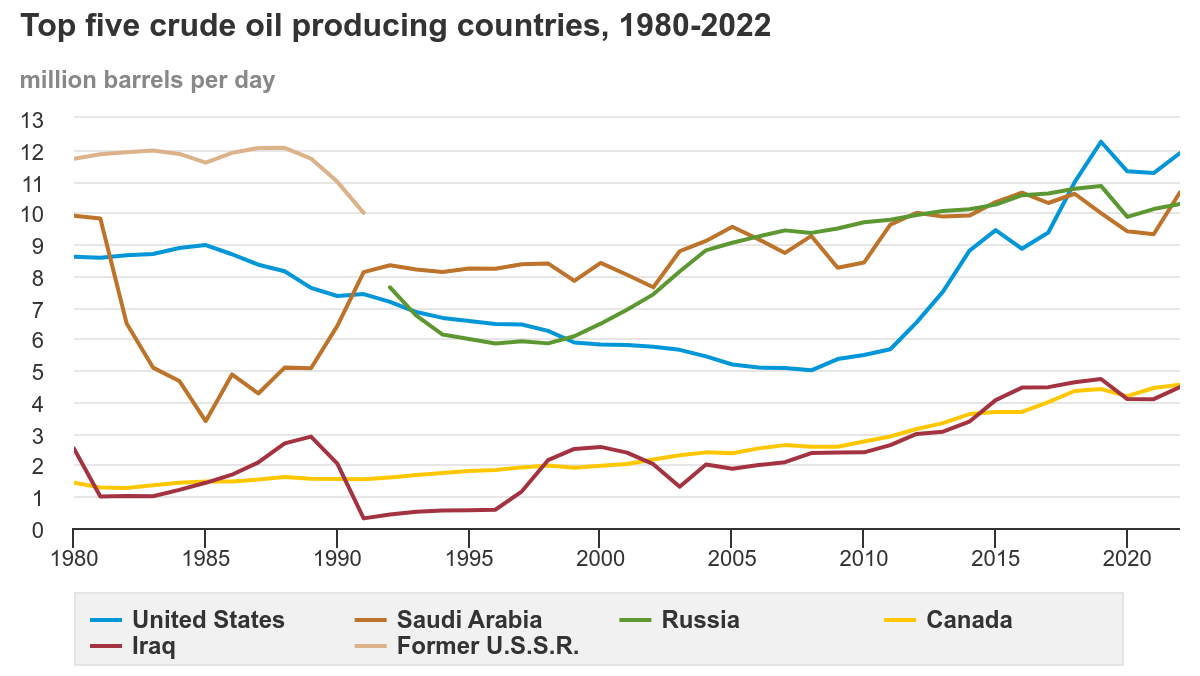

In 2015, hydraulically fractured wells accounted for 67 percent of U.S. natural gas production and 51 percent of U.S. crude oil production

Ballotpedia's encyclopedic coverage of fracking and energy policy in the United States. Ballotpedia: The Encyclopedia of American Politics

ballotpedia.org