- Joined

- Aug 10, 2013

- Messages

- 25,450

- Reaction score

- 32,400

- Location

- Cambridge, MA

- Gender

- Male

- Political Leaning

- Slightly Liberal

With the Affordable Care Act's 15th birthday coming up on Sunday (my, how time flies!), lots of retrospective pieces are starting to pop up.

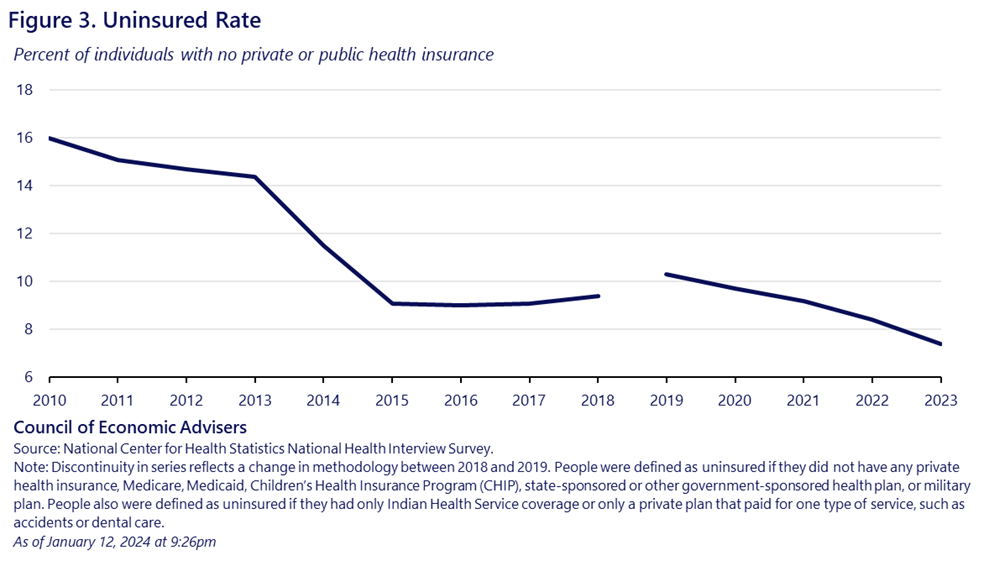

Despite plenty of unfinished business, the basic facts are worthy of celebration. Uninsurance plummeted, hitting an all-time low in 2023, with 45 million Americans insured directly under options created by the ACA last year. Health care cost growth since the ACA passed has been the lowest on record--the only sustained period of bending the cost curve ever. And the demonstrable positive impacts on quality and people's health outcomes have been quite exciting.

But the implementation has been a rocky experience, with lots of twists and turns. What have we learned? Three potential takeaways:

The Affordable Care Act At Fifteen: Policy Surprises And Lessons

I agree with those, though the third one is kind of nuanced. But if Dems had known how much health care cost growth would plummet and how much more important more generous subsidies were than an individual mandate, the last 15 years could have been quite different politically.

Lots more learnings one could add to the list, but for me it's the perhaps underappreciated overriding importance of income inequality. Despite the ACA being perhaps the biggest inequality reducing piece of legislation in decades, something upstream of it still seems broken. If you had told me 15 years ago that the cost curve would bend (something I didn't think would happen until the 2020s) and that per capita health care costs would fall as a portion of disposable per capita income, I would have imagined most people would feel that. But it doesn't seem to have registered, which suggests that the 'real' problem is potentially one of inequality, if arresting (or even reversing on a per capita income basis) health cost growth still leaves people feeling left behind. Still musing on that one.

Despite plenty of unfinished business, the basic facts are worthy of celebration. Uninsurance plummeted, hitting an all-time low in 2023, with 45 million Americans insured directly under options created by the ACA last year. Health care cost growth since the ACA passed has been the lowest on record--the only sustained period of bending the cost curve ever. And the demonstrable positive impacts on quality and people's health outcomes have been quite exciting.

But the implementation has been a rocky experience, with lots of twists and turns. What have we learned? Three potential takeaways:

The Affordable Care Act At Fifteen: Policy Surprises And Lessons

The Individual Mandate Was Not Essential After All

Few parts of the ACA were more controversial than the “individual mandate.” During the 2008 Democratic primary, Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama clashed over the necessity of requiring individuals to buy health coverage if they could afford it. First introduced by Republicans in 1993, most experts and virtually all insurers viewed the mandate as essential to simultaneously requiring equal access to coverage for people with pre-existing conditions. Yet, it caused staunch allies to blanch during the 2009 Congressional debate and was subject to Constitutional challenges decided twice by the Supreme Court. Ultimately, the tax linked to the individual mandate was repealed as part of the massive Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2017. Even though discerning its impact amidst other changes is challenging, the foretold implosion of the individual market without the individual mandate did not occur.

Premium Tax Credits Have Been Extra Important

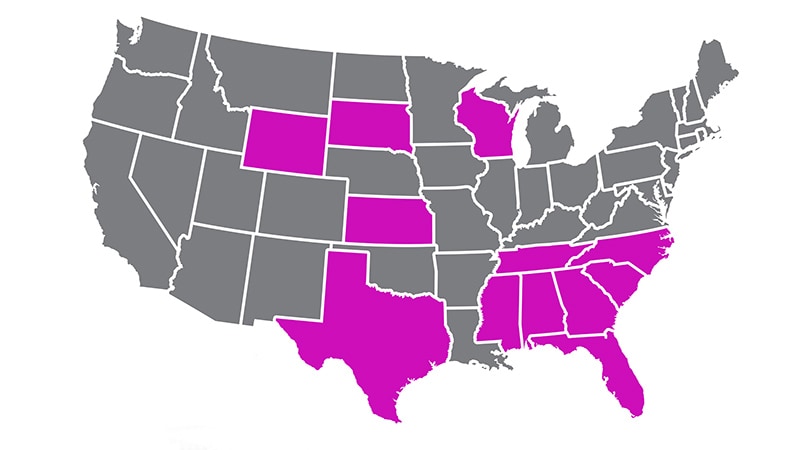

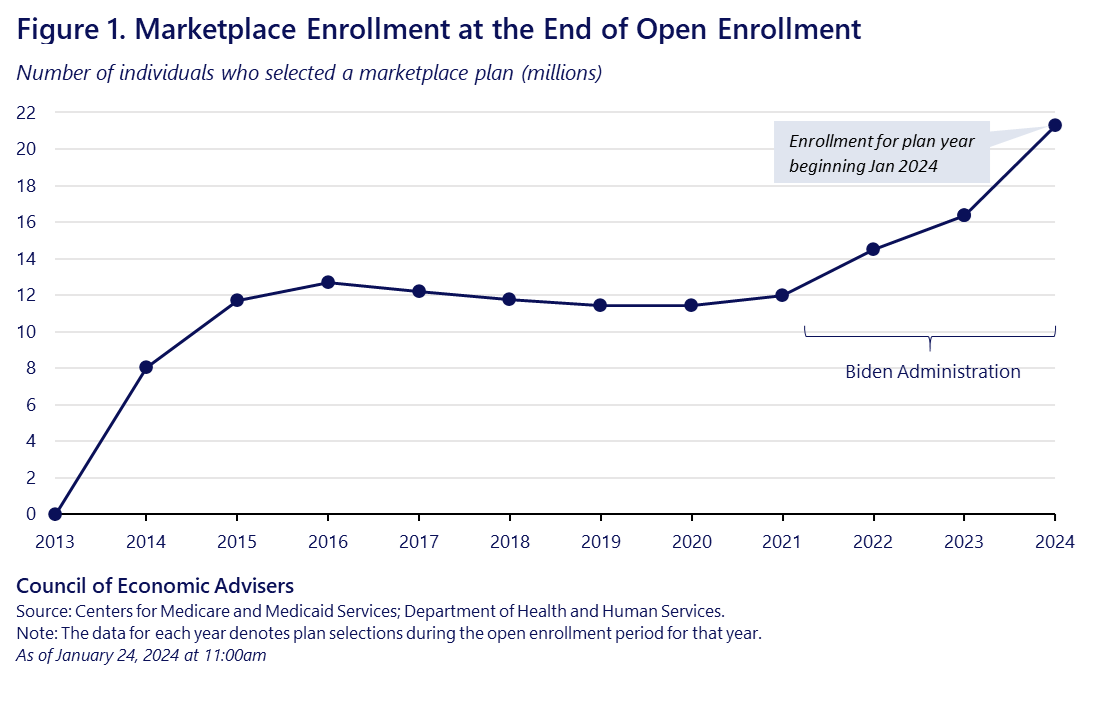

A second surprise has been the unexpectedly effective role of health insurance marketplace premium tax credits. At passage, these tax credits were viewed as important, although limited in value and constrained by eligibility floors and ceilings at 100 percent and 400 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). When the Trump administration ceased payments for cost sharing reductions in 2017, despite the ongoing requirement that insurers lower cost sharing for enrollees with income below 250 percent of FPL, the premium tax credits were able to absorb the cost through “silver loading.” Moreover, modifications to the tax credits in the 2021 American Rescue Plan, continued by the Inflation Reduction Act through 2025, contributed to a doubling of marketplace enrollment. This helped prevent major coverage loss after the COVID-19 pandemic, defying expectations, and achieve the original projected marketplace enrollment goal of 24 million. Congress must continue these tax credit changes in the coming months to prevent lower enrollment, higher premiums, and more uninsured Americans.

Fixing Rather Than Adding Programs Was More Effective

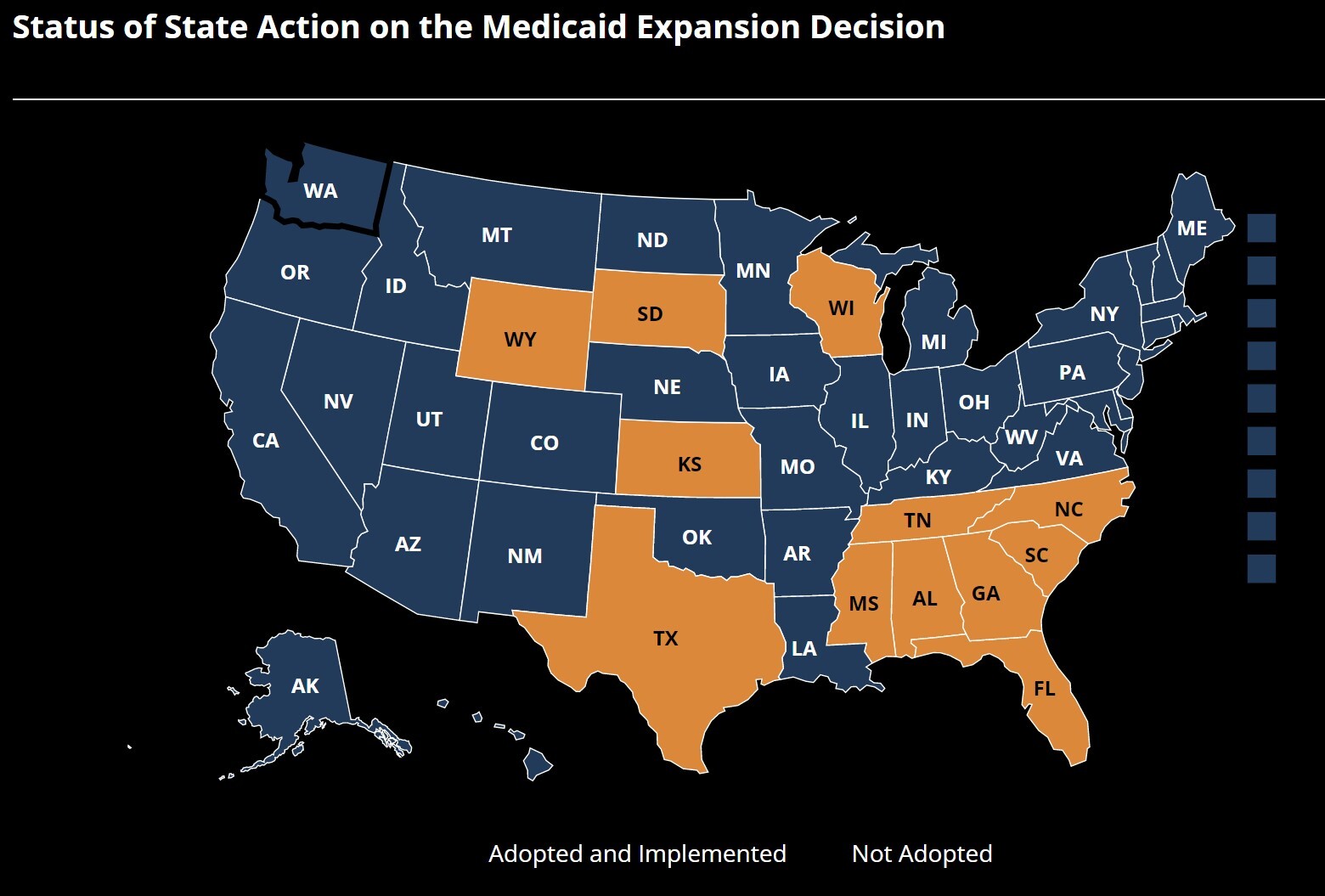

[...]While the limited impact of the high-risk pool program was not a total surprise, the massive amount of work for small gains was unexpected—as was the repeat across the ACA of changes to existing programs outperforming new programs. Other examples include the enduring benefit of consumer regulations in private insurance (e.g., medical loss ratios) versus the new consumer-run plan, COOPs, whose funding was repealed; and the greater impact of the statutory Medicare accountable care organizations versus the models added by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation. Part of the success in improving coverage, costs, and outcomes of the ACA’s Medicaid expansion is that it extended the existing program.

I agree with those, though the third one is kind of nuanced. But if Dems had known how much health care cost growth would plummet and how much more important more generous subsidies were than an individual mandate, the last 15 years could have been quite different politically.

Lots more learnings one could add to the list, but for me it's the perhaps underappreciated overriding importance of income inequality. Despite the ACA being perhaps the biggest inequality reducing piece of legislation in decades, something upstream of it still seems broken. If you had told me 15 years ago that the cost curve would bend (something I didn't think would happen until the 2020s) and that per capita health care costs would fall as a portion of disposable per capita income, I would have imagined most people would feel that. But it doesn't seem to have registered, which suggests that the 'real' problem is potentially one of inequality, if arresting (or even reversing on a per capita income basis) health cost growth still leaves people feeling left behind. Still musing on that one.