- Joined

- Sep 11, 2021

- Messages

- 18,826

- Reaction score

- 11,571

- Gender

- Undisclosed

- Political Leaning

- Very Liberal

My first priority is to increase the number of competitive seats in the US House. I will do that by drawing as many 50/50 districts as possible in each State, then “anti-gerrymandering” the remainder.

www.nationofchange.org

www.nationofchange.org

By the definition “over 5% margin is a safe seat” only 6% of House districts will be competitive in 2022. I can easily do better than that, using a redistricting algorithm to create an ANTI-GERRYMANDER.

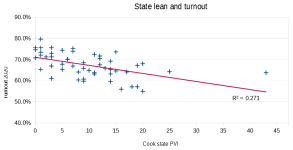

My second priority is that each state contingent should match the 2-party vote in that state. This takes no account of turnout in each district. Nor does the current system of course. West Virginia with 38% Democratic vote, should send a Democrat most years (1 of 3).

I made as many competitive districts as possible for the remaining districts to be no more than 90% towards the majority party in that state. If the algorithm can’t turn out such heavily gerrymandered districts, then we work backwards eliminating one competitive district at a time until "anti-gerrymandered" districts are possible for the remainder. It may be 80% or even 70%, in either case it’s unwinnable for the minority party.

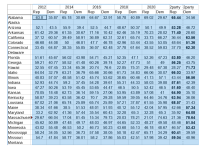

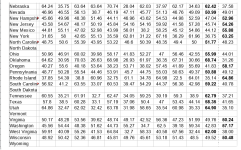

Consider the example of Hawaii. House results averaged over 5 elections (first and second tables, 2012 to 2020) and then adjusted to add to 100%. Republican candidates got only 28% of the vote, so NO DISTRICTS AT ALL can be made tossups. To make one tossup district would use up 25% of the R vote, and therefore I’m assuming no other district could be drawn (competitive OR anti-gerrymandered, since it’s a 2 district State). The system does work for 2 district states, but not if they're extremely partisan.

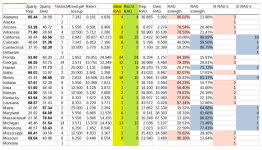

Another tricky example is California. With a perfect gerrymander it would be possible to have 38 tossup districts, however this would require 18 districts all with 2% R’s in them. The column “Adjusted Tossup (AT)” in the third table, shows 35 tossup districts instead, because this makes the Anti-Gerrymandered districts each 10% Republican, or greater. In this run-through, there are 15 anti-gerrymandered districts in California.

Note that 90% is an estimate of the maximum of majority voters who can be packed into one district. It will depend on the districting algorithm but the number will be higher in the deep red or deep blue States. It’s easier to gerrymander against the majority, than against the minority.

It’s planned that tossup states will come in a range within 5% of each other. Where there’s an even number of planned tossups, they would lean equal numbers and amounts each way, and where there’s an odd number of planned tossups, one district would be exactly 50/50.

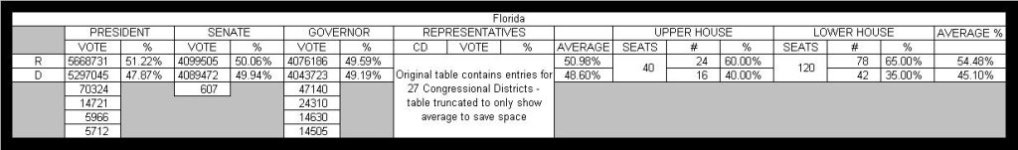

My system produces 314 tossup districts beginning two years after the Census year. Not counting single-district states (because I skipped them) nor Wisconsin nor Virginia (who had their Anti-Gerrymandered districts within 5% by chance), this is 72.2% of districts, being tossups. Objective 1 is attained!

It’s worth noting that demographics of each district change over one decade, and I’m not able to do anything about incumbency advantage during that time either. It’s still a lot better than what State districting has done for voters now.

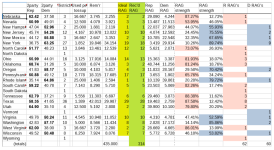

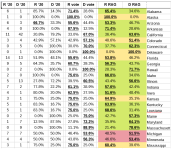

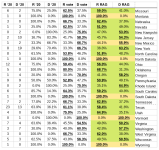

The second objective is state delegations looking like the statewide vote. This is given in Tables 4 and 5. Single district States appear as 100% with no further calculations. The second and third columns show actual representation in 2020. Columns 4 and 5 are the 2012-2020 votes per election and state (ie, using 2020 as a "random" example of future elections.) Seventh and eighth columns are the expected result if both parties ran “to form” for the last decade (ie prediction of my system).

You can see that almost every state elects more proportionately (green) using my system. Some are the same (yellow.) Michigan and Minnesota are worse, but not far off my prediction, and indicate a swing to Republicans in 2020 continuing to 2022. Both are within the 5% winnable margin (for the 7th or 4th district respectively).

I was actually surprised this turned out so well. With states representing the vote so well, it follows naturally that the US House as a whole will be more representational too: Republicans 215, Democrats 220. That’s not biased: Republicans only need a national swing of less than 1% to take the House. It's how it should be.

It is possible to make winnable districts for third parties. However, it’s also necessary for those third parties to contest more than one election in a decade. Until they do that, it is not justified to make a three-way winnable district for their benefit. A third party with 3% of the vote, don't get their 3% of representation without a full overhaul of the House with a national list of candidates. My system is not that radical: the only change is to how districts are drawn.

Just 6% of US House seats expected to be competitive thanks to rigged maps | NationofChange

By the definition “over 5% margin is a safe seat” only 6% of House districts will be competitive in 2022. I can easily do better than that, using a redistricting algorithm to create an ANTI-GERRYMANDER.

My second priority is that each state contingent should match the 2-party vote in that state. This takes no account of turnout in each district. Nor does the current system of course. West Virginia with 38% Democratic vote, should send a Democrat most years (1 of 3).

I made as many competitive districts as possible for the remaining districts to be no more than 90% towards the majority party in that state. If the algorithm can’t turn out such heavily gerrymandered districts, then we work backwards eliminating one competitive district at a time until "anti-gerrymandered" districts are possible for the remainder. It may be 80% or even 70%, in either case it’s unwinnable for the minority party.

Consider the example of Hawaii. House results averaged over 5 elections (first and second tables, 2012 to 2020) and then adjusted to add to 100%. Republican candidates got only 28% of the vote, so NO DISTRICTS AT ALL can be made tossups. To make one tossup district would use up 25% of the R vote, and therefore I’m assuming no other district could be drawn (competitive OR anti-gerrymandered, since it’s a 2 district State). The system does work for 2 district states, but not if they're extremely partisan.

Another tricky example is California. With a perfect gerrymander it would be possible to have 38 tossup districts, however this would require 18 districts all with 2% R’s in them. The column “Adjusted Tossup (AT)” in the third table, shows 35 tossup districts instead, because this makes the Anti-Gerrymandered districts each 10% Republican, or greater. In this run-through, there are 15 anti-gerrymandered districts in California.

Note that 90% is an estimate of the maximum of majority voters who can be packed into one district. It will depend on the districting algorithm but the number will be higher in the deep red or deep blue States. It’s easier to gerrymander against the majority, than against the minority.

It’s planned that tossup states will come in a range within 5% of each other. Where there’s an even number of planned tossups, they would lean equal numbers and amounts each way, and where there’s an odd number of planned tossups, one district would be exactly 50/50.

My system produces 314 tossup districts beginning two years after the Census year. Not counting single-district states (because I skipped them) nor Wisconsin nor Virginia (who had their Anti-Gerrymandered districts within 5% by chance), this is 72.2% of districts, being tossups. Objective 1 is attained!

It’s worth noting that demographics of each district change over one decade, and I’m not able to do anything about incumbency advantage during that time either. It’s still a lot better than what State districting has done for voters now.

The second objective is state delegations looking like the statewide vote. This is given in Tables 4 and 5. Single district States appear as 100% with no further calculations. The second and third columns show actual representation in 2020. Columns 4 and 5 are the 2012-2020 votes per election and state (ie, using 2020 as a "random" example of future elections.) Seventh and eighth columns are the expected result if both parties ran “to form” for the last decade (ie prediction of my system).

You can see that almost every state elects more proportionately (green) using my system. Some are the same (yellow.) Michigan and Minnesota are worse, but not far off my prediction, and indicate a swing to Republicans in 2020 continuing to 2022. Both are within the 5% winnable margin (for the 7th or 4th district respectively).

I was actually surprised this turned out so well. With states representing the vote so well, it follows naturally that the US House as a whole will be more representational too: Republicans 215, Democrats 220. That’s not biased: Republicans only need a national swing of less than 1% to take the House. It's how it should be.

It is possible to make winnable districts for third parties. However, it’s also necessary for those third parties to contest more than one election in a decade. Until they do that, it is not justified to make a three-way winnable district for their benefit. A third party with 3% of the vote, don't get their 3% of representation without a full overhaul of the House with a national list of candidates. My system is not that radical: the only change is to how districts are drawn.