For

context:

Marx and Engels asserted that women’s emancipation would follow the abolition of private property, allowing the family to be a union of individuals within which relations between the sexes would be “a purely private affair.” Building on this legacy, Lenin imagined a future when unpaid housework and child care would be replaced by communal dining rooms, nurseries, kindergartens, and other industries. The issue was so central to the revolutionary program that the Bolsheviks published decrees establishing civil marriage and divorce soon after the October Revolution, in December 1917. These first steps were intended to replace Russia’s family laws with a new legal framework that would encourage more egalitarian sexual and social relations.

(ibid.):

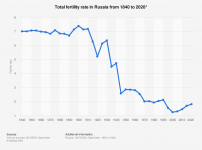

As Janet Evans has argued, “Women appeared to feel exploited by the advent of the ‘new morality’ in the 1920s,” caught off guard by the sudden changes in sexual behavior, in attitudes toward marriage and divorce, and in the devaluing of motherhood that came with the expectation that women’s work outside the home was synonymous with independence. While most letters printed in newspapers during the discussion supported the draft law, the voices of opposition were significant. “It was no coincidence that the Soviet government guaranteed parental responsibility at the same moment that it outlawed abortion,” David Hoffmann has argued in his analysis of Stalinist pronatalism. “They therefore sought to buttress the family as a positive incentive for women to have more children, at the same time that they instituted coercive measures to prevent abortions.” After a limited, temporary increase in the number of births, in 1938 the birthrate began to decline again and did not rise to pre-industrialization levels, calling into question the effectiveness of the decree as a pronatalist measure.

(ibid.):

Like Fedotova, many letter writers addressed the financial hardship caused by the laws regarding alimony, which they considered to be unfair. Soviet family law in the Stalin era allowed for the very real possibility that an alimony suit brought against a relative could cause the financial ruin of families. This was due in part to the fact that alimony law was written explicitly in favor of abandoned single mothers, shifting the burden of proof to their male lovers—and unintentionally burdening the other members of these men’s families. Fedotova concluded her letter with a warning: “It has reached the point that men have begun to avoid women, in each of whom they see the inclination toward alimony.” Presenting Soviet alimony law as a force favoring single women, destroying men’s trust in women, and therefore undermining families, Fedotova narrated a scenario in which registered marriages and legitimate children were threatened by alimony-hunting single mothers.

If you don't want to read the entire article, it fairly summarizes how the early Soviet policies (pre-Stalinist era) took a hatchet to families with progressive social policies, and that in spite of decades of subsequent attempts to repair the damage (i.e. "buttress the family") by repealing the policies--even subsiding childbirth--many of the most damaging laws remained in effect until well after Khrushchev.

See also:

Glowaki et al.