Debt Debate Rages On

Main Points

- There is a fundamental misunderstanding not only about debt’s role in the economy, but also the current state of the federal debt and deficit.

- Debt itself should not be ascribed any ethical connotations, as it is not inherently “good” or “bad”. Debt should be viewed in terms of usefulness, i.e. the use of it’s proceeds.

- National governments are fundamentally different entities than private sector households or businesses, including their purpose of organization, role in the economy, and position in the capital markets.

- The spending and debt of a national government plays a critical role in a country’s economic policy. Debt management needs to be in sync with the needs of the economy and society.

- The recent uproar over the sustainability of the United States’ federal debt is largely misplaced; as evidenced by the strength of our currency and the reception of record treasury issuance by investors. There is no doubt in our minds that the U.S. has the ability and willingness to pay its debts.

In the Sunday NY Times Letters section on July 28th there was a

series of letters debating the issue of debt levels in the US, whether they were dangerous or not and whether our outstanding debts needed to be repaid. The authors of the letters all had reasonable arguments for supporting their claims, probably feeling that they were at least somewhat “well informed” about the issues at hand. One of them had formerly worked at the Fed. However, as one might expect given the difficulty of addressing such a large set of issues in such a short space, there was little that the average reader could conclude about this issue based on the arguments being made. The purpose of this piece was to comment on the points raised in the article.

Utility of Debt

Debt is neither inherently good nor bad; absolute levels of debt are not inherently benign or frightening; and the purposes to which debt is used vary from critically necessary to frivolous. Government debt in particular is often discussed in ominous tones, with connotations of unprincipled profligacy. The most popular theme centers on trying to equate government spending to that of a household - comparing the debt racked up in Washington to that of a reckless shopper who maxes out their credit cards. While the sentiment behind this notion is perfectly understandable - if consumers are being forced to cut back, shouldn’t the government have to do the same – such an argument ignores the critical role federal debt plays in a capitalist society, from providing a foundation for risk in capital markets to replacing collapsed private borrowing during periods of economic slack and high unemployment (as well as providing for our defense, building our infrastructure and funding our social safety net).

Whether the borrower is a household, a business or the government, we generally regard the distinction between “good debt” and “bad debt” as whether the proceeds are used for needed (or superfluous) investment or consumption. When a new couple finances the purchase their first home, the use of debt allows them to make a productive investment in their future by building equity in an asset that will retain its value. When a company needs to increase manufacturing to keep up with growing customer demand, the use of debt allows them to make an investment in a new factory and grow their business. When a local city government needs money to build a new sewer system or bridge, debt facilitates them to make a productive investment in the city’s core infrastructure. These are all examples of debt being used for productive purposes. The contrary to this would be our previous example of a reckless shopper who maxes out their credit card, a business that uses debt to finance wasteful expenses, or a corrupt politician who uses debt to finance fancy dinners or expensive retreats.

Willingness and ability to pay: Looking at the letters from the NY Times we are struck by how much political rancor and hostility there apparently is surrounding debt levels in the United States. To defuse some of this anger, let’s try instead to look at our debt obligations from the perspective of a financial analyst trying to determine if the US is a good credit. You would only want to buy a bond where the borrower has the ability and willingness to pay back its debts. By this fundamental measure, our debt levels do not warrant concerns. Elements that go into this analysis include:

Three C’s of Credit

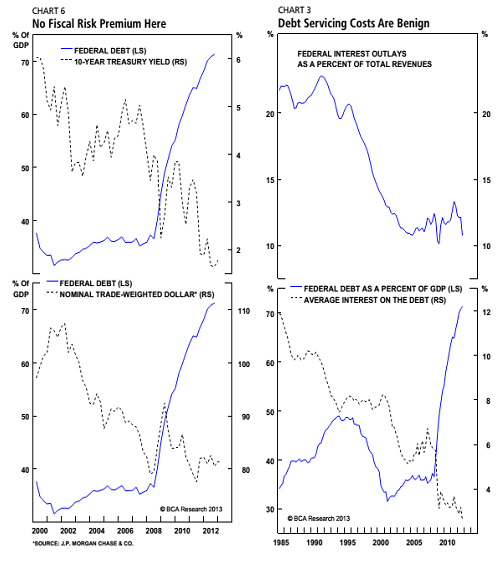

Character – While a more qualitative metric, the character of a borrower is a key consideration of lenders in fundamental credit analysis. While no person in their right mind would consider nearly any government on the planet as having “character”, there are certain corollaries that are worth mentioning. We believe one of the most important factors in sovereign debt sustainability is the stability of the country’s political, financial, and legal system. This is why historically one of the main causes of sovereign debt default in the past has been war. Countries with strong legal systems provide borrowers with proper recourse in the case of default, stable political systems allow for confidence that politicians will honor their obligations, and developed financial systems provide proper liquidity in the country’s currency and debt. The measure of the market’s perception of this character is most appropriately represented by the strength and status of their currency and credit default swaps on its debt. Two stark examples of the importance of character actually happened very recently, most famously in 2010 when Greece was found to be cooking their books by understating their true debt, and when the U.S. almost defaulted due to the debt ceiling negotiations in 2011. Both of these cases had significant ramifications for the bond markets and they both had very little to do with any traditional measure such as Debt/GDP.

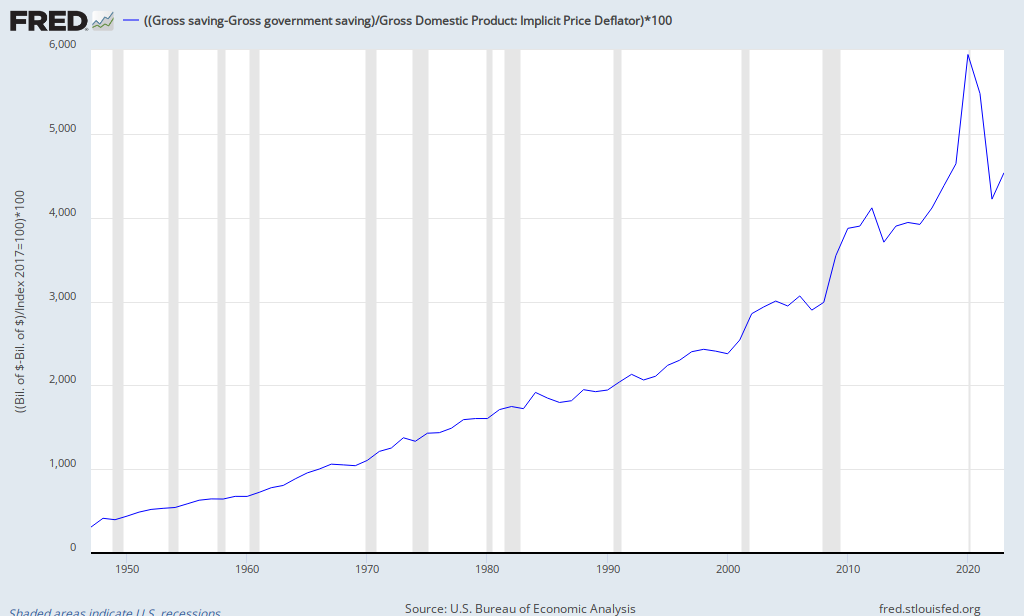

Capital/Collateral (Debt/GDP) – Another fundamental of investing in debt is determining the quality or adequacy of a borrower’s capital or productive assets relative to the borrower’s level of debts. Here too, we do not believe that current US debt levels warrant concern. US total Federal debt stands at about 104% of GDP. By comparison Japan has debt to GDP in excess of 240%, more than twice as high as the US. In neither of these two cases do markets appear to be concerned about these debt levels – again as measured by either the currency markets or credit default swap markets. Why not? Simple: because both countries are rich, with enormous pools of intellectual and productive capital. The US has $16.7 trillion in outstanding federal debts (marketable and non-marketable), but also has annual GDP of over $16 trillion and an estimated total household net worth of close to $69.3 trillion dollars (after subtracting out Treasuries).

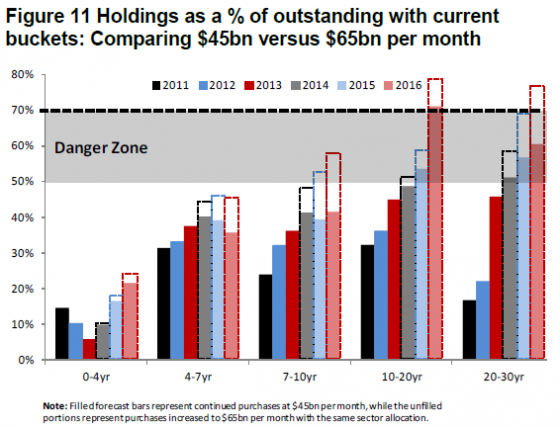

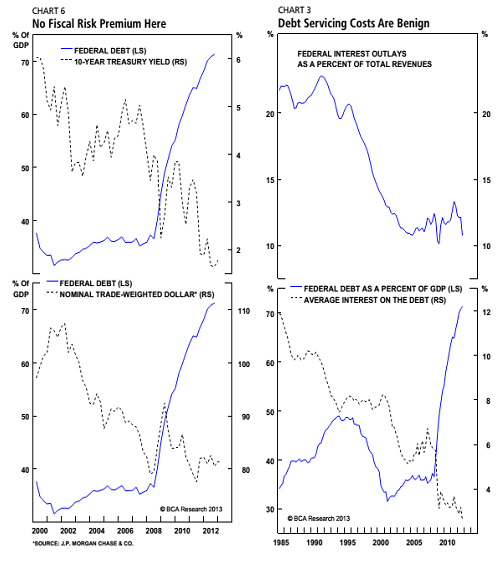

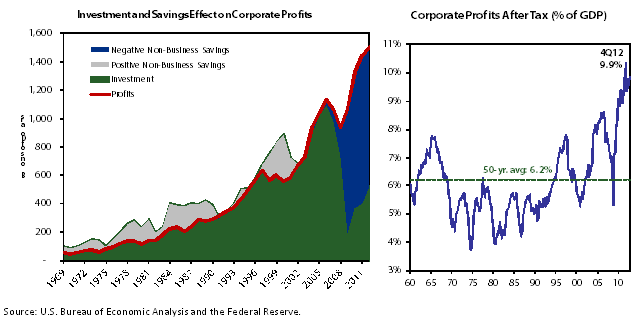

Capacity (Coverage, Interest Rates) – Perhaps one of the most important factors in credit analysis is the capacity of the borrower to honor their obligations. Measures of capacity primarily focus on the ability of the borrower to meet interest payments with ongoing cash flow. The capacity of a country to meet their obligations depends primarily on two factors. The first is the amount being spent on interest payments relative to various measures of wealth and cash flow. As the accompanying charts show, while the total amount of federal debt has clearly grown rapidly, our debt service costs as a percentage of the federal budget are at multi-decade lows - with federal interest charges as a portion of the Federal budget at 50% of their 1990 levels. Stated differently, our debt service cost in 2012 was $220 billion on a federal budget of $3.5 trillion or just 6% of outlays; and as a percentage of US GDP, debt service was a very small 1.3% of our $16.3 trillion in GDP . Simply put, given the size of our economy, we can handle our debts. Obviously as interest rates rise, the burden of this debt will increase (and we are not saying that debts should be allowed to grow without limit). But this is why it is so important to grow our economy; so that we will continue to have additional resources when they are needed.

The second, and probably most important, is the ability to print money. Technically, countries like the U.S. and Japan cannot be forced to default on their debt since their debt is all denominated in their own currency, of which they are the sole manufacturer. While the issue of debt monetization can jeopardize a country’s reputation (character) and may have other ill side-effects such as financial instability and inflation; the fact is that the U.S. government can never have a shortage of dollars needed to meet their obligations. This is another key area that makes analogies to Greece incorrect. One of the primary reasons for the runaway debt crisis in Greece was the government’s inability to print Euros, which disabled them from doing anything to contend with market forces. By all these current measures, we feel certain that the United States has the willingness and ability to meet its debts, and will continue to have that ability going forward given the current track of a growing economy and a rapidly shrinking budget deficit.

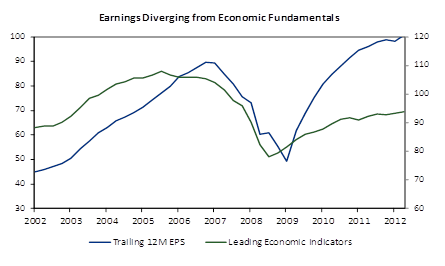

So do we need to borrow more or pay down our debts? The recent argument over debt has been simplified and exaggerated by both sides of the debate; with one side claiming that in the current environment that there is no limit on our ability to borrow, and the other side claiming that we are fast approaching a point of no return. In order to maintain a healthy and competitive economy over the long-term, debts cannot grow faster than incomes for very long periods of time . So there are limits. However, in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis there is still an abundance of idle resources that the private sector is unable to put to work; with banks afraid to lend, leaving households and businesses forced to curtail capital spending and investment. In this environment, interest rates have already been driven to zero by the Fed, so the only remaining lever that we have to promote growth is additional fiscal stimulus. The risk here is not that we have too much debt, but that we have too little activity. It is precisely in this environment where the economy is extremely sensitive to changes in fiscal policy. Here is where the federal government’s role is crucial – they can issue debt at very low interest rates (providing a place for people to invest their capital without fear of losing it) and invest it in both productive resources and consumption that not only creates jobs in the short-run but generates long-term benefits for the economy over the years to come. In fact, cutting back spending in attempt to reduce Debt/GDP has clearly already failed for the distressed countries of Europe (GIIPS) and we expect to see these policies changing before year’s end. In times of stress we need to continue to spend on productive endeavors, but we still need to spend on our defense as well as on our social safety net. The alternatives are too dire.

Conclusion: In hard times such as 2008, when the increase of federal debt was largely driven by a collapse in the private sector, the government was right to increase spending and cut taxes in an effort to make up for the shortfall in private sector investment and to make it easier for consumer who had seen a collapse in their incomes. The increases in US debt since then have been constantly criticized. While the maximum sustainable level of sovereign debt is impossible to quantify, our discussion above should give comfort that current levels are clearly sustainable. So where is the limit and how close are we to it? We believe that advanced countries, with sovereign monetary policy and floating exchange rate currencies are given long runways by the market. We don’t believe we are close to a point where the US would go bankrupt or see its debt markets disrupted, and we don’t believe that current levels of federal debt should be a primary concern in a period of low inflation, high unemployment and sluggish growth. We also don’t think we need to be focused on reducing our debt/GDP right now. Save that for the days when GDP growth is back above 5% and we’re at full employment (and then actually repay some of the debt). The debt issue is also less of an concern when the government is effectively borrowing at negative interest rates – as it is today for most of its borrowings. Borrowing at negative rates means that the government is profiting from its borrowings! It remains true that it is important to make sure the debt grows slower than our economy in the times that warrant it. Therefore, the extremes on both sides of the political debate are wrong; we believe that both the tax/regulate/anti-Fed crowd and the austerity/hard-money crowd are driven more by ideology than by proper economic policy. The focus of the debt debate should be on what the purpose of the debt creation is for, and what times are appropriate for the government to use debt as a tool for promoting a better society and a stronger economy.